by Leon J. Podles –

by Leon J. Podles –

Modern Christians don’t deny Death, although they don’t like to think about it, and if they believe in an afterlife, they look forward to a pleasant Heaven. However, the other certainty, Judgment, and the other possibility, Hell, have vanished from the minds of Christians.

Surely God is non-judgmental, as non-judgmentalism is one of the few virtues that receive public tribute. And surely no one goes to hell, if it exists. The strong universalist strain in modern Christianity has many variations, ranging from the hope that all will be saved, held by Hans Urs von Balthasar, Richard John Neuhaus, and perhaps by John Paul II (and with which I feel the deepest sympathy), to a total rejection of the doctrine of hell as a patriarchal trick that thwarts self-liberation.

However, the traditional teaching on hell is in fact a sign of the genuineness of Christianity, and it is therefore a cause for hope. Liberal Christianity is largely a human construct; it is what happens to a revealed religion after human beings finish redecorating it to modern tastes.

H. Richard Niebuhr summarized the liberal gospel: “A God without wrath brought men without sin into a kingdom without judgment through the ministrations of a Christ without a Cross.” However, the darker parts of the Gospels are a sign of their genuineness, because they are not what we would have made up if we were inventing a religion to satisfy our desires. Promises of comfort on this earth, yes; promises of eternal bliss, yes; even viewing earthly troubles (whose existence can scarcely be denied) as an educational tool to discipline us and to make us grow spiritually, yes; but threats of eternal punishment, fires that are not quenched, and worms that do not die—no, no, no.

liberal gospel: “A God without wrath brought men without sin into a kingdom without judgment through the ministrations of a Christ without a Cross.”

The fires and worms have been eliminated to make Christianity less dark, but the darkness guarantees that the Faith is a divine Word, and not a human construct. The gospel is good news, evangelion, like the imperial proclamations, not because it makes us comfortable but because it is an announcement from the innermost heart of a reality that is itself beyond our comprehension, a message we could never have dreamed of ourselves, even though creation contains hints and foreboding and dark promises.

As to who goes to hell . . . Jesus was asked, “Are there many who will be saved?” He does not answer the question directly but uses it to make his point: He is the only way, and there are few who find it. Whether he finds those who do not find him, he does not say. Saints and theologians differ on this, and I am neither. But I will venture a few of my reflections.

Perhaps human decisions sometimes do determine our identity, insofar as we have committed so much of ourselves to them that if an outside force changed our decision, we, as individual persons, would be destroyed. That is, if God forced a person to repent, he would not really be the same person. God still loves the person even when that person rejects him; he therefore will not force the person to repent, because he would no longer be the same person.

Judgment, then, is inescapable, because it is simply the truth revealed.

Judgment, then, is inescapable, because it is simply the truth revealed. The utter clarity of the uncreated Light reveals to us the truth about ourselves, but it will not be comfortable for us when we no longer see in a glass darkly but face to face. We all know some of our faults—if we are married, our spouses will be happy to enlighten us about others—but there are some, probably the most serious, that are unknown except to God. Even an orthodox Christian who tries to observe the moral law perhaps has hidden pride of which he is unaware. Others, who do not have such light, do terrible things in a good conscience: abort children, gas Jews, fly passenger planes into skyscrapers. When we finally see ourselves fully in the Divine Light, the experience will be very painful for all of us, even for the just, and excruciatingly painful for us sinners. Catholics call it purgatory; Orthodox and some Protestants do not give it a name but admit the reality.

What of those who see their sin for what it is, a rejection of God, and still embrace it? Can God force them to reject sin and accept his mercy, without making them different persons? That may be a logical contradiction, like a squared circle or a thing better than God.

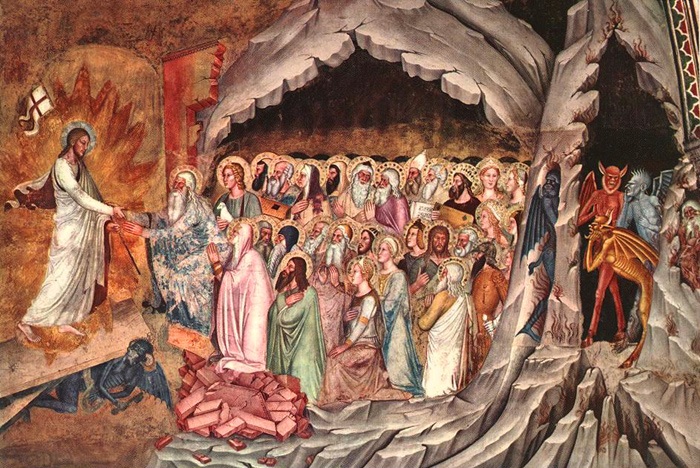

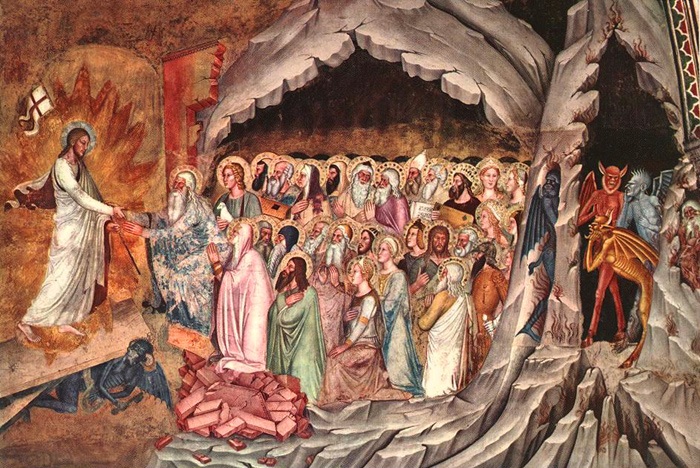

God allows this final rejection of him, if the person in full knowledge still embraces the sin, because he loves even the damned. He could annihilate the demons and the damned, but he chooses not to, because he still loves them. To them, that love is a terrible fire; to the repentant, it is at first a purging fire and then endless light. Even the damned are not punished as much as they deserve; an Orthodox prayer (Akathist for the Departed) claims that even the pagans in Hades are comforted by our prayers. Therefore, those Christians who pray for the dead (and whatever abuses it may lead to, it is a deeply human impulse) exclude none from their prayers. While we are uncertain of their fate, our love, like God’s, should extend to all.

God can be nothing else than Love, even if that creating and sustaining love becomes unendurable to those who reject it. Hell is not something we would put in a universe we constructed according to our human desires, but that is only because our understanding and our love are both weak. We do not see the depths of the human soul and the mysteries of love that endures beyond all rejection. The revelation of salvation and damnation does not have the sentimental sweetness of human wish-fulfillment, but the astringent and sobering taste of reality.

HT: Touchstonre