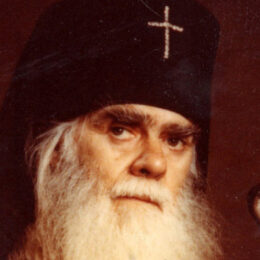

by Archbishop Charles Chaput –

by Archbishop Charles Chaput –

If human laws do not reflect the deeper law of God, there is little chance of survival. That is why people of faith must participate in politics and public life because the current culture rejects God’s law or even Natural Law as a foundation for our society.

We now come to our third point: The law can’t teach effectively without the support of a surrounding moral culture, because law arises from that culture. As many thinkers, including St. John Paul II, have recognized, culture precedes politics and law. Law embodies and advances a culture, especially its moral aspects.

We Christians need to keep this in mind as we work for justice in our societies, despite the very negative climate of today’s culture wars. We should use political means as fruitfully as we can, without apologies. We should seek and employ political influence in our work on vital issues like marriage and family, abortion, immigration and euthanasia. And it’s right and just that we do so.

But, as Cardinal Avery Dulles once noted, culture wars can’t be won by tactical battles, even on crucial issues such as these. Policy statements by bishops and advocacy by lay men and women have important value. But their words, said the cardinal, “must be backed up by a coherent social and political philosophy.”

In the long run, Dulles wrote, “if a consensus exists in favor of a healthy society, the implementation will almost take care of itself.” Again, Dulles never suggested that we should abandon the political arena.

the battle for hearts and minds runs deeper than winning a particular issue at the polling booths.

Nor do I – quite the opposite. But we need to remember that the battle for hearts and minds runs deeper than winning a particular issue at the polling booths. Conversion is more important, and much more far-reaching, than any particular legislative debate.

Now, it’s easy to say that positive law should be grounded in natural law. And positive law does clearly reveal a lot about a culture. So, good cultures should logically have good laws and bad cultures should have bad ones – right? But real life is more complex.

In Canada and the United States, we have a long legacy of many good man-made laws founded on principles of natural law. And they’re often still in force. But these laws no longer enjoy the cultural consensus that made them. A new, unfriendly cultural consensus demands that they be redefined or dumped altogether.

It’s helpful to know where this new consensus came from. So I want to mention very briefly two political philosophers: the French scholar Pierre Manent, and again, Eric Voegelin.

Manent argues that modern life – the “modern project” – grounds itself on the power of the human will to transform the world around us. Obviously, humans have always known that they could change the world to some degree.

God can be mocked, but in the end, his order can’t actually be overturned.

But the ancients were more aware of their limits. They were also more modest in their ambitions. They held that we need to reconcile ourselves to an existing order of nature that, even if flawed, is still essentially good.

And in recognizing nature’s limits and the need to conform to its order, they found real freedom. Moderns see the world very differently. Modern life “frees” us from thinking that we need to conform to any natural order – or even from believing a natural order exists.

In Aristotle’s time, men and women saw the natural purpose of marriage — its telos — and they tried to pursue it, however imperfectly. Moderns also look at marriage. They want marriage to be different. So they work to reshape it according to their will.

And since we’ve lost our understanding of an objective human nature and moral order, the desires of our will very quickly take on the mantle of “human rights” that others may not interfere with it.

the Gnostic effort at remaking reality will always fail because the order of being cannot, in fact, be changed

The reason so many moderns seek to change the order they find in the world is that they experience it as confining or unjust. Eric Voegelin notes that the more modern men and women seek to re-create the natural order, they more they need to remove God from its head.

In this resentment of the natural order and in the attempt to change it through the human will, Voegelin sees a new form of the Gnosticism that Christianity has fought from its birth. And yet the Gnostic effort at remaking reality will always fail because the order of being cannot, in fact, be changed: As Voegelin says,

The closure of the soul in modern Gnosticism can repress the truth of the soul, as well as the experiences that manifest themselves in philosophy and Christianity, but it cannot remove the soul and its transcendence from the structure of reality.

This explains the bitterness of the voices that seek to discredit God in our own time. It also explains the savagery of the totalitarian regimes of the last century. God can be mocked, but in the end, his order can’t actually be overturned.

we need to remind people of the truths they’ve forgotten, the truths on which our society is founded.

Where does this leave us as Christians?

As in every other age, we’re called to preach Jesus Christ to our fellow citizens. We need to learn for ourselves and be ready to teach others the truth about the human person, the objective foundation of morality in the natural law. We need to fight to keep our human laws obedient to that deeper law. And we need to remind people of the truths they’ve forgotten, the truths on which our society is founded.

As then-Cardinal Ratzinger once wrote, the moral convictions that undergird the United States — and, I would argue, Canada . . .

… demand corresponding human attitudes, but these attitudes cannot flourish unless the historical basis of a culture and the ethical-religious insights that it preserves are taken seriously. A culture and a nation that cuts itself off from the great ethical and religious forces of its own history, commits suicide.

He continues,

The cultivation of essential moral insights, preserving and protecting these as a common possession but without imposing them by force, seems to be one condition for the continued existence of freedom in the face of all [of today’s] nihilisms and their totalitarian consequences. It is here that I see the public task of the Christian churches in today’s world. It accords with the nature of the Church that [she] is separated from the state and that [her] faith may not be imposed by the state but is based on convictions that are freely arrived at.

Ratzinger closes with a quotation from Origen:

Christ does not win victory over anyone who does not wish it. He conquers only by convincing, for he is the Word of God.

This is part II of Archbishop Chaput’s speech on Law and Morality at the Faith in the Public Square Conference in Toronto. Part I can be found here.

HT: CatholicismUSA