by Anthony Esolen –

by Anthony Esolen –

I recently observed that there must be something odd about someone who likes to play Naming of Parts with the children of strangers, whether it’s a slobbering bachelor down the street who’s friendly with one kid, or a minor governmental functionary who is friendly with two dozen. For suggesting that parents and not slobs or schoolteachers have the sole authority to teach their children about sex, I was called “bizarre.”

Get used to it, comrades. The collapse of moral values is now shifting into a mad inversion. It used to be considered evil to deprive a child of a mother or a father. It will now be considered evil to insist that a child should have a mother and a father. It used to be considered evil to walk naked in front of children. It will now be considered evil to demand that people stay clothed in front of children.

We will have to adapt to our inverted times that most powerful scene in the Gospels. “This woman,” say the crowds, “has been caught teaching her children that sex is for marriage! What shall we do with her?”

“Give her a dose of medicine,” says the Prince of this world, tossing a rock in one hand, and holding a hypodermic needle in the other.

Call us crazy, but there are plenty of madmen in our asylum, and they have names like Dante, Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, Johnson, Aristotle, Plato, Cicero, Augustine, Pascal, Tolstoy, and Dostoyevsky.

No sane person before the day before yesterday believed what we are supposed to believe now, about men and women, marriage, the education of children, the role of the State, the insignificance of the church, and the cramped little corner left for faith. Call us crazy, but there are plenty of madmen in our asylum, and they have names like Dante, Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, Johnson, Aristotle, Plato, Cicero, Augustine, Pascal, Tolstoy, and Dostoyevsky.

These are our allies. With only a few exceptions, all of the great western poets and novelists who wrote before the twentieth century, and a majority of the greatest of those who wrote in that strange time, are our allies. Most are Christian, some are not. They are not nihilists, which is another way of saying that they are not ideologues. They do not try to cram reality into the narrow prison of an Idea. They do not hate intractable mankind. They do not hate men for being men or women for being women. They do not have what Burke called the most purely evil thing in existence, the heart of a metaphysician – by which he meant the heart of an ideologue, such as those who would soon clot the drains of Paris with blood.

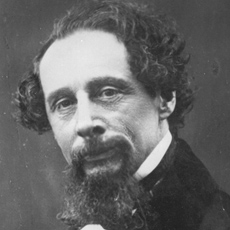

So let me introduce you to an ally who was, as a dear friend of mine puts it, “in love with goodness.” He is the greatest of English novelists, bequeathing to us all manner of human beings who have ever graced or disgraced the earth. No novelist has his boundless reach: the good and evil, clever and muddled, wise and foolish and sometimes both; Mr. Micawber, Cap’n Cuttle, Fagin the Viper, Silas Wegg, Sam Weller, Mrs. Jellyby, Betsy Trotwood, Miss Havisham, characters so sharply drawn that they become our companions for life.

Dickens was steeped in the gospels, and sometimes a gospel verse becomes the touchstone for an entire novel.

He writes with gusto; he captures the peculiarities of his characters in every possible way. “Shake me up, shake me up, Judy!” cries Grandfather Smallweed the loan shark, a crippled old man slumping in his chair. “I am ‘umble, Master Copperfield,” says Uriah Heep in his soft, fawning, sinister voice. “Something – I daresay I feel it is inevitable – something will turn up,” says Mr. Micawber, amiable and utterly irresponsible.

Dickens was steeped in the gospels, and sometimes a gospel verse becomes the touchstone for an entire novel. “I am the resurrection and the life,” saith the Lord; the whole of A Tale of Two Cities leads to that climactic moment, when Sydney Carton is “recalled to life,” finding his life by losing it for his friend.

“And he took a little child and set him in their midst,” reads Peter Cratchit to his brothers and sisters, as Scrooge and the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come look on, with the crutch of Tiny Tim lovingly preserved in a corner. The same Scrooge, turning away from his deadly evil, wakes up on Christmas morning as it were born again, crying out, “I don’t know anything at all. I am quite a baby!”

“Our Father, which art in Heaven,” says Doctor Woodcourt to the street boy Jo, doing the only thing he can do in the boy’s last moments, teaching him to pray as he dies of smallpox and exposure.

The spirit of the gospels is the spirit of his works: he is always writing with the works and words of Jesus in his blood and bones.

Whatsoever you do to the least of these, that you do unto me. The first shall be last, and the last shall be first. Come to me, all ye who labor and are heavy burdened, and I will give you rest. It is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God. Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth. Blessed are the clean of heart, for they shall see God. Love your enemies, do good to those who persecute you. The Son of Man came to call sinners. Nothing is hidden but shall come to light. Not by bread alone doth man live, but by every word that cometh forth from the mouth of God. I am the Good Shepherd; I know my sheep, and my sheep know me.

It’s not that Dickens salts his novels with sermons; nothing so superficial. The spirit of the gospels is the spirit of his works: he is always writing with the works and words of Jesus in his blood and bones. He gives us not only his memorable zanies, but the great of heart, so active and sensitive and human in doing good that they themselves are unaware of it: Sam Weller (the first among them, and an utterly new character in English literature), Mark Tapley, Esther Summerson, Mr. Boffin, Florence Dombey, Cissy Jupe, Mr. Peggotty, Lizzie Hexam . . . the list goes on.

You can and should teach your children what it is to be clean, honest, gallant, modest, industrious, and gentle.

You can and should teach your children what it is to be clean, honest, gallant, modest, industrious, and gentle. All that will be abstraction, chaff blown away by one gust of a song from the gutter, unless it comes embodied, in flesh and blood, with a voice, a look in the eye, and a firm grasp of the hand. Charles Dickens gives us that good company.

HT: LifeSiteNews