by Mark Tapson –

by Mark Tapson –

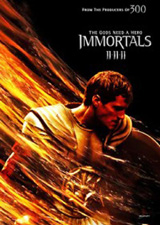

More and more, Hollywood has alienated audiences with its messages of moral equivalence and its clichéd insistence on casting corporate capitalists, the CIA, and Christian hypocrites as the bad guys in thrillers, action movies, and even horror flicks. It seems that the only genres in which fed-up moviegoers can still find old-fashioned faceoffs of good versus evil are some comic book adaptations like Captain America: The First Avenger and sword-and-sandal epics like Gladiator and 300.

That timeless confrontation of light and darkness is the explicit theme of the recent stylish, spectacular 3-D action adventure Immortals, from the unique dreamscape imagination of Tarsem Singh. Singh is a former director of music videos, best-known for his video of the REM song “Losing My Religion” and the nightmarishly surreal Jennifer Lopez film The Cell .

Immortals is set more than a thousand years before Christ in a mythic Greece overseen by Zeus and the other gods from their perch on Mt. Olympus. On earth below, the power-mad butcher King Hyperion, played by Academy Award nominee Mickey Rourke (The Wrestler) leads his dark army on a rampage across the land in search of the Virgin Oracle (Freida Pinto of Oscar winner Slumdog Millionaire). He knows that her disturbing visions can guide him to the secret location of the Bow of Epirus. The Bow has the power to unleash the imprisoned Titans, rivals to the gods; once they are freed, war in heaven will ensue, the gods will be cut down, and King Hyperion will rule heaven and earth. [Warning: mild spoilers ahead]

But the Virgin Oracle recognizes that an heroic young stonemason named Theseus is destined to rise up against Hyperion in an apocalyptic showdown for the future of humanity, and she throws her support behind him. Theseus (played by Henry Cavill, who will also star as Superman in the upcoming movie Man of Steel) doesn’t believe in visions or the gods, but he is fearless, and his mentor, a friendly old man played by Oscar nominee John Hurt of The Elephant Man fame, has instilled in him the notion that “living itself is not as important as living rightly”:

All men’s souls are immortal, but the righteous man’s soul is immortal and divine.

Little does Theseus know that the old man is merely the mortal shell of Zeus, who is confident that if any mortal can stand up to Hyperion, it’s Theseus. The young peasant has a personal motivation as well: he seeks revenge against Hyperion for murdering his mother before his very eyes. He assembles a ragtag band of followers and embraces his destiny.

He may be fearless, but in Hyperion’s horde, Theseus is up against an enemy whose “belief allows them to kill without restraint,” who “honor no rules of engagement,” who represent “a terrible darkness.” Sound familiar? Whether or not the screenwriters or director Tarsem intended it, this description surely resonates with anyone today who is cognizant of the worldwide threat posed by Islamic fundamentalists, who love death more than we love life, who offer only subjugation or death to infidels and apostates, who proudly wear the label “terrorists,” and whose totalitarian vision of the caliphate is a “terrible darkness” indeed.

Theseus has witnessed Hyperion’s uncompromising evil firsthand. He warns his king Cassander to “seal the gates and prepare for war.” But Cassander clings to his smug certainty that, as the bumper sticker says, “war is not the answer” and that “negotiations and reason” will prevail – a stance that sounds admirable in theory but is viable only if one’s enemy is committed to the same ideals. Unfortunately for Cassander, war is precisely the answer to everything for Hyperion and his killers. He insists on being reasonable and offering to negotiate right up to the very second that Hyperion wordlessly relieves him of his clueless head.

In the face of Hyperion’s army, Cassander’s warriors lose heart and panic. It takes a rousing speech from Theseus about what it is they are fighting for to inspire them to arms. An epic clash ensues. In the process of his path from peasant to legend, Theseus finds his religious faith and proves that even peasants can earn honor and immortality through their righteous deeds.

This is no children’s movie with cartoonish, bloodless violence. It’s disturbingly dark and the violence is sometimes cringe-inducing. There is copious bloodletting and more impalings, beheadings, throat slittings, exploding heads, eye-gougings, and full-body cleavings than one can count. “War,” as John Stuart Mill put it, “is an ugly thing.”

But not the ugliest of things. Immortals comes from the producers of 300, the epic retelling of the famed tiny force of ancient Spartans who perished to the last man defending a narrow mountain pass against an overwhelmingly larger force of invading Persians. The debt this new film owes to 300 is significant, not only visually but thematically. Their message is that we must stand ready to be righteous warriors in defense of our families, our homes, and our way of life, and that dialogue and negotiation with evil is suicide. As Mill famously wrote:

The person who has nothing for which he is willing to fight, nothing which is more important than his own personal safety, is a miserable creature and has no chance of being free unless made and kept so by the exertions of better men than himself.

Considering the challenges that we in the democratic West face from enemies within and without, Theseus’ call to arms in Immortals is as relevant today as at any time in history.

HT: FrontPage Mag