by Quin Hillyer –

by Quin Hillyer –

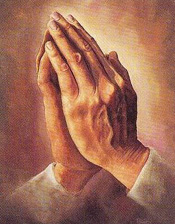

Pray. Really. Pray. Praying might just be what we need if we want this blessed country to thrive as a beacon of freedom.

It’s always a bit of a risk, and can be borderline off-putting, to intertwine prayer and politics in an overt way, or even to seem to do so. Readers or listeners rightly recoil when somebody suggests that God takes sides in politics, or that his (the person’s) own politics are more godly than that of his opponents, or (worse) that he undertook his own candidacy or cause because God “told” him to do so. That’s not what this is about. This also isn’t one of those “the-sky-is-falling” sorts of rants in which the point is that the nation is somehow on the verge of utter disaster and can be saved only by openly miraculous, divine intervention. Things aren’t great in the good’ol USA right now, but we’re not (quite) at that extremity yet.

Instead, at issue here is something more subtle. At issue is a country that has lost its way, in part because far too many millions of its individual citizens have lost their own way in their daily lives. The full litany of ills is so familiar that anything more than a sample list of them would be boring: out-of-wedlock pregnancies, abortions, hideously trashy prime-time TV shows, raunchy music, attire in public that isn’t just slovenly but scandalous, casual acceptance of financial cheating… and more, ad infinitum. Another, less-recognized sin is that of a certain form of sloth, which shows itself in declining standards across the board — as evidenced, for just one example, in this week’s story (similar to dozens of other stories on such subjects in the past two decades) about just how pathetically American children do on tests of the most basic historical (or civic-related) information. (What gets lost in this case is any sort of common culture, or at least a common culture with more depth and value than Survivor and “Dancing with the Stars.)

The “lost way” also shows itself — if personal, unscientific observation is to be believed — in declining church attendance, at least in many denominations; and in the declining role of faith in individual lives, as measured more formally by polls and surveys. It certainly shows itself in our politics, which — even for people whose idealism has been tempered by decades in the fray — seems more disjointed, dysfunctional, and petty than ever. In a constitutional republic that for 224 years really has worked remarkably well to reflect the character and collective sensibilities of its citizens, politics that have grown unusually dysfunctional and atomized can be assumed to signal a populace likewise more dysfunctional and atomized than in previous eras. After so many years of working far better than not, our Madisonian system can be assumed not to have suddenly stopped working; instead, it works all too well to show how flawed we as a people may have become.

We also are the most generous people on Earth, the most consistently productive people on Earth, and have done more good for humankind than any other nation in the history of the world. We still do so, every day.

None of which is to deny that we as Americans retain strengths, collectively and individually, that still can make us a beacon for the world. Gloom and doom are not our ordinary attributes, and certainly not the point here. We also are the most generous people on Earth, the most consistently productive people on Earth, and have done more good for humankind than any other nation in the history of the world. We still do so, every day.

The problem is that we seem to do so with less confidence than before — with predictably less impressive results, on many fronts — and that the lack of confidence seems to come as much from our souls as from our conscious wills. While we do not suffer from a Jimmy Carter-like malaise, we nevertheless do not, individually or collectively, project or own best selves into the international or domestic public arenas with the same surety or verve as we once did. (It doesn’t help, of course, that we have a president who thinks it a virtue to “lead from behind,” but that isn’t what this really is about.) The signs, greater and lesser, are all around us: The dollar begins to lose its status as the world’s reserve currency; our diplomatic efforts are met with at least as much disdain as respect; our manufactured products and even our culture are less popular or valued than they were 20 years ago; and even our athletes (tennis, golf, baseball, track) not only fail to dominate as they once did but actually get dominated, repeatedly, in open competition.

Only wisdom can help us determine right from wrong

We need renewal. And the renewal must be far more substantive than vague (and cynical) appeals to “hope and change.” We also need wisdom, a commodity that seems in short supply. Knowledge and know-how, technological adeptness and social networking: These won’t do. Wisdom is something different, deeper, more profound and more personally challenging than those other attributes. Only wisdom can help us determine right from wrong not just in daily life but in the civic realm; only wisdom can help us distinguish demagoguery from reason; only wisdom can help us choose servants instead of self-seekers to lead us.

This is where prayer comes in.

We should not pray for our candidates to win. We should not pray for our side to prevail. We should not pray for our goals to be met, our desires satisfied, our issues handled the way we want, or for God to block the paths of our adversaries. Down that road, again, lies the temptation to confuse, even in all sincerity, our own wills for God’s will. It is hardly original to point out that the Kingdom of God is not a program of social reform, and that we should not mistake our own reformist aims for His.

But we should pray, with all due devotion and humility, for wisdom. We should pray for wisdom and for the means of virtue, and for the forgiveness when we fall so that we can return to virtue and wisdom again. If we have wisdom and virtue in our own life, we will have the wherewithal to build better communities, and with better communities we will have the wherewithal to build a better polity.

I am a citizen of the United States of America. I love my country, and I will defend the Constitution of this great nation. I believe that America was founded upon Judeo-Christian values that must be maintained as prescribed by our founding fathers.

It so happens that the University of Mobile (full disclosure: with which I am now professionally associated, but that’s NOT why I wrote this column) is leading an initiative called the “twelve23 Movement” that is expressly dedicated to the sort of renewal this nation needs. It includes a pledge that begins thusly: “I am a citizen of the United States of America. I love my country, and I will defend the Constitution of this great nation. I believe that America was founded upon Judeo-Christian values that must be maintained as prescribed by our founding fathers.” The pledge ends like this: “Therefore, as one who loves this country, I pledge my honor to God and my allegiance to America. I commit to lead our nation to the concepts for which our founding fathers were willing to die — a government by the people and the exercise of individual liberty — with firm reliance upon Almighty God.”

We could all do worse than to take to heart, and live the values of, twelve23.

As for prayer in general, we need to pray because it will take wisdom of a profound sort — the sort hard to attain without a divine spark — for us to do the things we need, and make the choices we need, to renew America. As C.S. Lewis wrote in his book The Grand Miracle, “So much for the decline of religion, now for a Christian revival.” Later in the book: “As Christians we are tempted to make unnecessary concessions to those outside the faith. We give in too much. Now, I don’t mean that we should run the risk of making a nuisance of ourselves by witnessing at improper times, but there comes a time when we must show that we disagree…. We cannot remain silent or we concede everything away.” And: “The great thing is to be found at one’s post as a child of God, living each day as though it were our last, but planning as though our world might last a hundred years.”

To that I would only add that for civic purposes, we must broaden Lewis’s discussion to encompass not merely Christianity, but the larger Judeo-Christian ethos to which we are heirs. We pray to the same God the Father, and we are also heirs to the same promise of joy. But both personally and in community, that promise cannot be fulfilled if we do not pray for discernment, guidance and, yes, a wisdom beyond ordinary human ken.

HT: American Spectator (read full article)